| Select

a day

|

__

|

| |

| The Track & Field ("Athletics") event was held

at the Nepstadion (that is, the People's Stadium) in Pest, the

largest stadium in Hungary. Once you find the entrance (one

of the Australians put it well: "We always knew where we were,

it's just that the buildings got lost!"), it opens up before

you and you get a real sense of how large it is. |

|

| One person having a very good day at Nepstadion

was Iija Ignatiew of Finland (at left in photo). Not only did

she win two gold medals today (in 100 meters and high jump),

not only is she happy to be alive, but today was her 33rd birthday,

too! |

|

| Around 1989, Iija began to get sick with primary

pulmonary hypertension. As a youngster, and until the age of

22, she had been involved in track events as a member of an

athletic club. Unfortunately, because she was always athletic

and upbeat, her symptoms were not obvious. Only after her heart

was affected did the doctors realize that her lungs had been

quite damaged. She was quite sick, confined to a wheelchair,

unable to pick up her fifteen month old daughter, unable to

do even the simplest task for herself. She found it very frustrating.

By the time Iija was put on the waiting list, she didn't even

have enough energy to have any strong emotions; she was never

really happy, never really angry, she was just existing. |

|

|

While Iija waited three and a half weeks for a heart and

lungs, the doctors were predicting that she would die within

two weeks if the transplant didn't arrive. She was so desperate

that she thought that even if the transplant gave her just

a few more months of life, it would be worth it.

|

|

| Fortunately, it has given her five extra years of life, for

which she is very grateful. Even though she suffered several

bouts of rejection and problems with infections after the transplant,

she has overall done very well. Iija appreciates every day she's

given, and is very happy to be alive. |

|

| When she was sick, she said to herself "If I could

just run the 500 meter one more time, I would be so happy."

Now she runs whenever she gets the chance, including the Finland

National Transplant Games, the EuroTransplant Games, the Scandinavian

Transplant Games, and previous World Transplant Games. In Sydney,

she won two silver medals (100 meter and long jump), and one

bronze (200 meters). |

|

| When asked why she decided to come to Budapest,

she replied, "...to be with people who can really understand

what life is like after transplantation. And to win! Also, I

have always wanted to win three gold medals, so maybe tomorrow!"

Iija has two more events on Sunday, so she may get her birthday

wish! |

|

| I also met Brett Jones, a ten- year-old Australian who was

introduced by his father as "a medical miracle." Brett was born

without an immune system. At the time, there were only about

twenty other such cases and the doctors gave him a very grim

prognosis. After getting a bone marrow transplant at the age

of one in 1990, Brett has done very well. In Sydney at the XI

World Transplant Games, he competed in five events. Brett is

pleased to be here in Budapest, where he is the youngest boy

taking part in the Games. Brett's father, Stephen Jones, has

become a fundraiser for children's hospitals and has started

a fundraising organization for sick kids called "Kids Like Brett."

Brett is taking home at least one bronze medal from today's

competition. (Brett is at the far right in the group photo.) |

|

|

Two Italian competitors, Giovanni Antichi and Carolina Panico,

were camped out in the cool green grass in the field in the

center of the stadium, watching the races. I asked them why

they came to the Games, and they said "We love sports, we

love people, and we want to help people learn about donation,

to help people who are waiting for transplants." Giovanni

received a kidney transplant five years ago (in 1994), lives

in Savona (near Genoa), and is competing in skittles, swimming,

and volleyball. Carolina had a kidney transplant fifteen years

ago (in 1984), lives in Naples, and is competing in volleyball,

skittles, and bicycling.

In addition, Carolina wrote this message for our viewers:

|

|

|

(which is roughly translated as: "I hope that the 12,000

people in Italy who are on the waiting list will get the real

opportunity to be with us at the next Games, so that we can

enjoy them together!") Hear, hear!

|

|

|

Foils and Sabers Under

the Dome

Story

by Robert

Garypie

Photography by Gary Green and

Peter Ottlakan

Audio by Douglas

Armstrong

VIEW

RESULTS when available

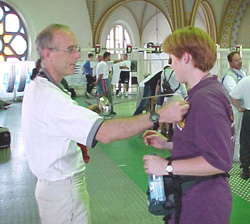

On the top floor of a converted synagogue, the fencing was

underway when we arrived. The domed ceiling of the competition

room at this venue is painted in blue, yellow, red, and beige

geometric patterns. The building was a synagogue until World

War II. It then became a storage facility until 1989. Then

the building came to life again as a sports facility. The

large stained glass windows are still in place, tinting the

beams of sunlight shades of blue and yellow.

|

|

|

Gary Green, TransWeb volunteer and World Transplant Games

Federation Councillor, patiently described the competition

to onlookers. According to Gary, accidental fencing injuries

are rare but can be fatal. Gary has been fencing for twenty

years; his tour in the Peace Corps drew on his knowledge of

fencing as he was assigned to coach the Chilean Olympic team

a few years back.

|

|

|

Today's competitors become instantly anonymous once they

put on their protective equipment. A black mesh face guard

disguises all emotion and expression. On the electrified metal

floor, points are scored when one's weapon contacts the torso

of the opponent.

With long wires running from the walls to the competitors,

lights and buzzers come to life when contact is made. Each

fencer has three wires that connect to the scoring computer

on the wall. One for his torso-area jacket, and two from his

weapon. Scoring is based on using the tip of the weapon to

strike the torso of the opponent.

The men and women from Hungary, Australia and USA were fencing

for ten hits to win each match. The round robin competition

allowed every competitor to meet all the others at some point

in the day. At the Olympic level, Hungarian saber teams are

famously successful and today's officials were Hungarian fencing

Olympians.

|

|

|

Two American men, one Australian woman, one Hungarian woman

and two Hungarian men participated.

Peter Cappuccilli of Team USA, hailing from Rhode Island,

took a silver and a bronze for Team USA. A kidney recipient,

Cappuccilli was cheered on by his son at the event. After

losing to Gyorgy Szekely of Hungary, who is also the president

of the local Transplant Games organizing committee, Cappuccilli

remarked, "In the last half of that bout he began to really

fence, which is what I wanted." Just prior to the medals ceremony

I asked Cappuccilli how he liked competing in Budapest. "Are

you kidding? It's great! My son is here with me -- he just

graduated from college -- and I get to spend five days with

him in Budapest. He lives in Florida and the two of us travelled

here together. It's just great!"

Having begun fencing just a year ago, Cappuccilli is thrilled

to be here. "Just wait two years -- I'll see you in Japan!"

|

|

|

The quiet of the medals ceremony room turned to a deafening

roar of clapping and cheering when the medals were presented.

Then the Hungarian national anthem was played and the crowd

fell silent again. Strains of Hungarians singing their anthem

filled the room.

In the corner, Dr. Joszef Ree, the Hungarian WTGF councillor,

stood and looked on. As the anthem reached its crescendo,

Ree (who was largely responsible for these Games' coming to

Budapest) looked around the room. A heartfelt smile slowly

crept across his face as he must have realized that all of

his hard work paid off. The athletes are here, the medals

are being awarded, and Budapest has become a great home for

the World Transplant Games.

|

|

|

|